Continuing my habit of publishing unpublished essays, here’s a critical analysis of ‘The Scream’ by Edvard Munch. Words written in 2003, pics and headings added for the the benefit of readers in 2011. Harvard referencing used throughout. If it looks like I’m stating the obvious that’s because academia demands it!

Introduction

The

Scream ( or The Cry as it is also known)

by Edvard Munch has been the subject of much analysis since it was first

displayed. As an artefact of ‘high ’ culture it is seen as great work of art,

while as a cultural product it has been widely referenced and reproduced.

“This is visual culture. It is not just a part of your

everyday life, it is your everyday

life.” (Mirzoeff, 1998: 3)

For humans,

sight is our most important sense, far more developed than any other. We tend

to privilege sight above other senses, which gives rise to the study of visual

culture. Berger (1972) says, “Seeing comes before words…the child looks and

recognises before it can speak.”

However, Welsch (2000) makes an interesting point about The

Scream which diminishes the impact of this

idea.

“Take Munch’s painting The Scream as example. You

haven’t actually perceived it until you’ve heard a scream – an

incessant scream which makes you tremble. Visual perception, in this case, must

proceed through to an acoustic one.” (Welsch, 2000)

Baldwin

et. al. (1999: 395, 366) explain that “Seeing is always cultured seeing…What we

see is always conditioned by what we know.” In this case, Welsch ’s argument can

be explained as such: to understand The Scream we must first have heard the sound of an anguished scream.

This essay aims to explain how culture effects how an image in seen.

Artist and production

The

Scream can be analysed it terms of the

context of its initial production, and the life of the artist.

Munch was born in 1863, and grew up in Norway ’s capital

Christiania, now called Oslo. He was the son of a military doctor, and nephew

of a Norwegian historian. Munch ’s early life was a tragic affair. His mother

and older sister both died of tuberculosis, while the only one of his siblings

to marry died soon after the event. Munch himself was frequently ill. He was

encouraged to be culturally active, and he used his art to express his feelings

about his experiences. He studied under Christian Krohg, Norway ’s leading

artist at the time, and his early influences were French Realist painters.

Around 1889 he became involved with the Kristiania (as Christiania was spelled

at this point) bohemians, a group of radical anarchists. Their leader, Hans

Jæger, taught Munch about modernism, and encouraged him to paint about the

longings and anxieties of the individual. In autumn 1889 his father died. The

sadness within Munch ’s life can be seen to have affected his work.

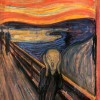

The

Scream was painted using tempera and

pastel on board. It depicts, at face value, one central figure who has his/her

hands over their ears while two figures walk into the distance. The scenery is

a sunset and a sea or river. The brush strokes cause the scene to appear to

swirl, giving it a sense of motion.

Expressionism/Existentialism

The Scream is thought of as the first expressionist painting.

The Web Museum (2002) defines expressionism as a “movement in fine arts that

emphasized the expression of inner experience rather than solely realistic

portrayal, seeking to depict not objective reality but the subjective emotions

and responses that objects and events arouse in the artist.” Munch ’s painting

does not show a realistic visual interpretation of reality; it is an abstract

image, based on his inner feelings, and attempts to convey his most intimate

and terrifying feelings and emotions. Munch made a diary entry in January 1892

which is widely associated with the creation of The Scream :

“I was

walking along the road with two

friends.

The sun

was setting.

I felt a

breath of melancholy –

Suddenly

the sky turned blood-red.

I

stopped, and leaned against the railing,

deathly

tired –

Looking

out across the flaming clouds that

hung like

blood and a sword

over the

blue-black fjord and town.

My

friends walked on – I stood there,

trembling

with fear.

And I sensed

a great, infinite scream pass through nature.”

(Munch,

1892)

What

would otherwise be a beautiful sunset if transformed into an expression of pure

dread, of anguish. Munch is said to have suffered severe depressions, which

would go some way to explaining the angst and horror conveyed in his art.

Munch ’s

portrayal of raw human emotion through art has led to him being labelled an

existentialist. This would seem to correlate with Jean-Paul Sartre ’s beliefs on

existentialism:

“The existentialist frankly states that man is in anguish.

His meaning is as follows When a man commits himself to anything, fully

realising that he is not only choosing what he will be, but is thereby at the

same time a legislator deciding for the whole of mankind – in such a moment a

man cannot escape from the sense of complete and profound responsibility. There

are many, indeed, who show no such anxiety. But we affirm that they are merely

disguising their anguish or are in flight from it.” (Sartre, 1946)

Munch,

in this context, could be seen to be struggling to come to terms with his

anguish, expressing it in terms of colour and shape.

An understanding of The Scream can be gained by looking at the period in history in which

Munch lived and worked. The end of the 19th century was a key

development period in modernist thought and existential philosophy, and the

writings of Nietzsche seem to link to the work of Munch. Nietzsche (1872)

believed art was born out of suffering, and any artist was a tragic character

to him.

“Innermost suffering makes the mind noble. Only that

deepest, slow and extended pain that burns inside of us as firewood it forces

us to go down into our depths… I doubt that such a pain could ever make us

feel better, but I know that it makes us deeper beings, it makes us ask more

rigorous and deeper questions to ourselves… Trust in life has disappeared.

Life itself has become a problem.” (Nietzsche, 1872)

The

science of the time was devoted to changing all that was once certain: for the

first time, people were questioning the authority of the Bible. Nietzsche

famously declared that “God is dead”, summing up the sense of loss and

hopelessness that many felt. Sartre shows that although this idea brings new

freedom to humanity, it also brings an enormous sense of uncertainty, resulting

in negative feelings:

“The existentialist…thinks it very distressing that God

does not exist, because all possibility of finding values in a heaven of ideas

disappears along with Him; there can no longer be a priori of God, since there is

no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it. Nowhere is it written that

the Good exists, that we must be honest, that we must not lie; because the fact

is that we are on a plane where there are only men. Dostoyevsky said, ‘If God

didn’t exist, everything would be possible ’. That is the very starting point of

existentialism. Indeed, everything is permissible if God does not exist, and as

a result man is forlorn, because neither within him nor without does he find

anything to cling to.” (Sartre, 1957)

Munch ’s

father is described as a religious man in most biographies of the artist.

Perhaps it is his childhood experience of religion, and his subsequent exposure

to modernist theories amongst the Kristiania bohemians, that caused conflict

within him. What was once a certainty for him, such as ideas of God and heaven,

were now outdated concepts to the modernists, and all that was left was the

suffering and anguish of a man without hope.

Context/Capitalism

The image was originally displayed in Berlin in 1893, as

part of a series of six paintings then called “Study for a Series Entitled

‘Love ’”. The original version of The Scream is now located in Norway ’s National Gallery in Oslo. This

can be seen as problematic. While art galleries are traditionally seen as a

‘natural ’ environment for the display of art, they remove the art from its

original context, if an original context can ever be located.

There is a long history

connecting art and western capitalism. Berger (1972: 84) showed that oil

paintings were used as commodities by middle and upper class traders as far

back as the 1500s. An internet search for the terms ‘Munch ’ and ‘Scream ’ will

generally produce two main types of website. A few will provide brief

descriptions of the painting as a ‘cultural icon ’ or ‘a great work of art ’, and

others feature biographies of the artist, but the vast majority of the sites at

this point in time are attempting to sell reproductions of the work. This can

be seen as highly indicative of the society in which we now live. Marx and

Engels (1848) might place our society at a point between middle and late

capitalism, since it blends reproduction and consumption as one.

However,

Munch was a noted printmaker himself:

“Edvard Munch is one of the twentieth century ’s

greatest printmakers, and his works—particularly The Scream and Madonna—have made their way into the popular culture

of our time” (www.yale.edu, 2002)

He

produced etchings,

lithographs, and woodcuts of many of his works himself, as well as new productions.

Perhaps he decided that a reproduction of a work filled with emotion could

still carry the same weight of meaning, and set about spreading his art.

Whatever the reasoning, Munch ’s work, particularly The Scream , is still in demand today,

and even reproductions can fetch a high price. But like Van Gogh ’s Sunflowers , The Scream can be bought very cheaply as

a printed paper poster and displayed anywhere, for example a bedroom door or

hallway, by virtually anyone, such is the availability and level of mass production.

‘The Scream’ in popular culture

The Scream has been

frequently referenced in popular culture since the rise of postmodernism.

Roland Barthes defined postmodern texts as “a multidimensional space in which a

variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash”, creating “a

tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture” (Barthes

1977: 146). Barthes argued that nothing is truly original, and all texts are

actually a mixture of different ideas, ‘quotations ’ as Barthes puts it, taken

from the culture that the author, and by association the consumer, inhabits,

and placed in a new context. The following examples are used to illustrate

this.

The 1996 ‘horror ’ film Scream makes a clear reference to The Scream , both in its very title and in the mask worn by the

killer.

“Sidney tries to lock herself in but the killer is already

in the house: a knife-wielding, black-robed figure wearing a mask based on

Munch ’s “The Scream” . (twtd.bluemountains.net.au, 2002)

This can be seen as a somewhat superficial use of postmodernity,

but a valid one all the same. Some might see it as an example of high art being

subverted by low art, but this would depend entirely on the viewer ’s reading of

the film, which isn ’t the goal of this essay. However, this use increased

interest in what was already a famous image. Replicas of the mask worn by the

killer in the film are mass-produced as movie memorabilia, and the image is

used on various other artefacts of merchandise from the film, creating a whole

section of culture which references Munch ’s original image.

In Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? (1968), the book which later became the film Blade Runner,

Philip K. Dick makes a reference to the image, giving another interpretation in

the process.

“At an oil painting Phil Resch halted, gazed intently. The

painting showed a hairless, oppressed creature with a head like an inverted

pear, its hands clapped in horror to its ears, its mouth open in a vast,

soundless scream. Twisted ripples of the creature ’s torment, echoes of it ’s

cry, flooded out into the air surrounding it; the man or woman, whichever it

was, had been contained by its own howl. It had covered its ears against its

own sound. The creature stood on a bridge and no one else was present; the

creature screamed in isolation. Cut off by-or despite-its outcry.” (Dick, 1968)

While some statements are seemingly incorrect (despite the

two other figures, the screaming figure could still be said to be alone,

depending on individual interpretation) the description almost certainly is of The

Scream , although probably a reproduction.

Resch stops because he wishes to understand, in the same way users of art

galleries stop to ponder the meanings of works. Dick seems to expect the reader

to be familiar with The Scream and

describes the image in such a way that, without seeing it, the reader

recognises what the character Resch does not. This suggests that for the

purposes of Dick ’s story, The Scream is

less culturally significant in the future.

Bronwyn Jones also uses the imagery of The

Scream ,

although in an entirely different context. Speaking about globalisation, she

states:

“In our millennial passage,

Carson’s “silent spring” could become the irony of Edvard Munch’s

silent scream transposed to a crowded room; all the channels are on, the

airwaves are humming, and no one can hear you.” (Jones, 1997)

Jones

alludes to Munch ’s existential nightmare, making a comparison with the

saturation of media around us, and the confusion it creates.

The Scream has

maintained popularity as an image for many reasons. Some believe it to be a

fine work of art from a pure ‘art history ’ perspective. The range of emotions

the image manages to portray in one silent scream captivates others. Whether

hanging in a gallery or taped to a teenager ’s bedroom door, the image is capable

of producing the same effects.

ReferencesBibliography

Baldwin, E. et al, (1999) Introducing

Cultural Studies, Hemel Hempstead: Prentice

Hall Europe.Barthes, R. (1977) Image-Music-Text, New York, Hill and Wang. 146Berger, J. (1972) Ways of Seeing, Harmondsworth: Penguin.Dick, P.K. (1996) Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, London: Random House. (orig. 1968)Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1967) The Communist Manifesto, Harmondsworth: Penguin (orig. 1848)Mirzoeff, N. (1998) What Is Visual Culture in Mirzoeff, N. (ed.) (1998) The Visual Culture Reader, London: Routledge.Nietzsche, F.(1967) The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Walter Kaufmann, New York: Vintage, (orig. 1872)Sartre, J-P. (1957) Being and Nothingness, London: Methuen.Art

Munch, E. (1893) The ScreamFilmography

Scream (1996) dir.

Wes CravenWebsites

Jones, B. (1997) State of

the Media Environment: What Might Rachel Carson Have to Say? retreived from

http://www.nrec.org/synapse42/syn42index.html (28/12/02)Sartre, J-P. (1946) Existentialism is a Humanism retrieved

from http://www.thecry.com/existentialism/sartre/existen.html (03/01/03)Welsch, W. (2000) Aesthetics Beyond Aesthetics retrieved

from

http://proxy.rz.uni-jena.de/welsch/Papers/beyond.html, (30/12/2002)Web Museum: http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/net/The Symbolist Prints Of Edvard Munch retrieved from http://www.yale.edu/yup/books/o69529.htm

(29/12/02)And You Call Yourself

AScientist! – Scream (1996) retrieved from http://twtd.bluemountains.net.au/Rick/liz_scream.htm

(29/12/2002)

, The Scream by Edvard Munch – a critical analysis www.ozeldersin.com bitirme tezi,ödev,proje dönem ödevi